Lab 08: Python Operators

Pull and Update in VS Code

Before starting any lab, you need to make sure that the repo in your GitHub is the latest one. Sync the repo if the upstream repo have been updated.

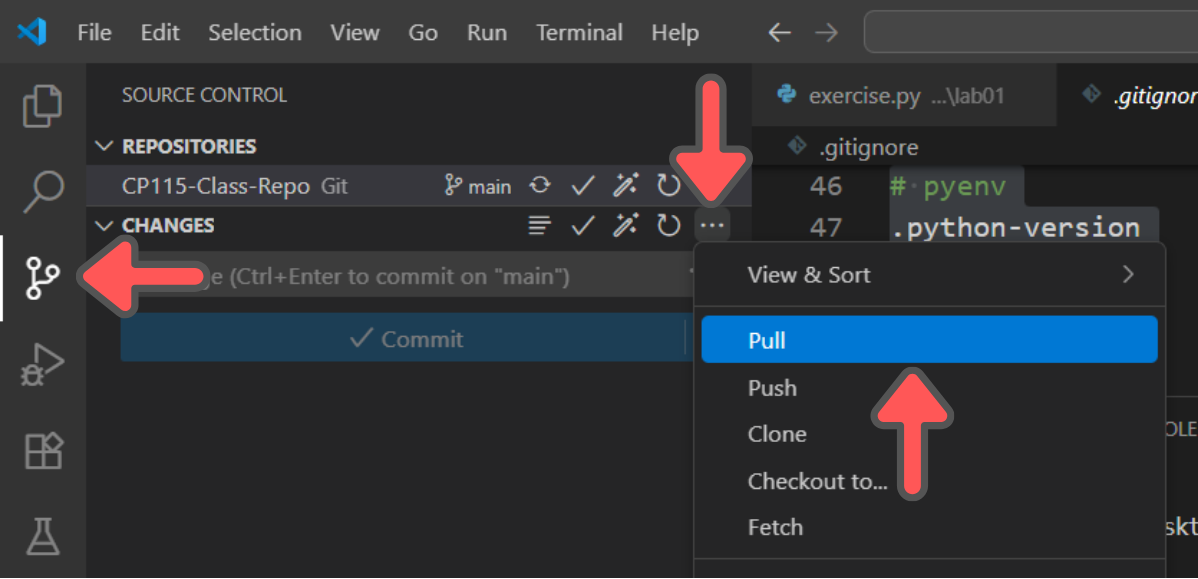

Once the online repo is in-sync, bring those changes down to your PC by clicking Source Control and then ... beside Changes and click Pull.

Python Operators

Python provides various operators to perform operations on data. These operators are essential building blocks for creating calculations and logic in your programs.

Launch VS Code and open the exercise.py file in /labs/lab08/. Let's explore different types of operators:

Arithmetic Operators

Arithmetic operators perform mathematical calculations:

| Operator | Description | Example | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

+ | Addition | 5 + 3 | 8 |

- | Subtraction | 10 - 4 | 6 |

* | Multiplication | 6 * 7 | 42 |

/ | Division (float) | 15 / 4 | 3.75 |

// | Floor Division | 15 // 4 | 3 |

% | Modulus (remainder) | 15 % 4 | 3 |

** | Exponentiation | 2 ** 3 | 8 |

In your exercise.py file, let's test each operator. Start by testing addition and subtraction:

# Test addition and subtraction

result1 = 25 + 15

result2 = 100 - 25

print(f"25 + 15 = {result1}")

print(f"100 - 25 = {result2}")Run this code and see what you get. Are the results what you expected?

Now add multiplication and division:

# Test multiplication and division

result3 = 8 * 7

result4 = 20 / 4

print(f"8 * 7 = {result3}")

print(f"20 / 4 = {result4}")Can you see the difference in the output? Notice how division gives you 5.0 instead of just 5. Why do you think that happens?

Finally, test floor division, modulus, and exponentiation:

# Test floor division, modulus, and powers

result5 = 17 // 5

result6 = 17 % 5

result7 = 3 ** 4

print(f"17 // 5 = {result5}")

print(f"17 % 5 = {result6}")

print(f"3 ** 4 = {result7}")Run this and observe the results. Can you figure out what 17 // 5 and 17 % 5 are doing? Think about dividing 17 by 5 - what's the whole number part and what's the remainder?

Type Casting in Operations

When performing operations, Python automatically determines the result's data type. Different operators can produce different types of results:

| Operation | Result Type | Example |

|---|---|---|

int + int | int | 5 + 3 = 8 (int) |

int + float | float | 5 + 3.0 = 8.0 (float) |

int / int | float | 10 / 2 = 5.0 (float) |

int // int | int | 10 // 3 = 3 (int) |

int ** int | int | 2 ** 3 = 8 (int) |

int % int | int | 17 % 5 = 2 (int) |

Let's test type casting in operations in your exercise.py. Test how different operations affect data types:

# Test division - always returns float

division = 10 / 2

print(f"10 / 2 = {division} (type: {type(division)})")

# Test floor division - returns int when both operands are int

floor_div = 10 // 3

print(f"10 // 3 = {floor_div} (type: {type(floor_div)})")

# Test modulus - returns int when both operands are int

modulus = 17 % 5

print(f"17 % 5 = {modulus} (type: {type(modulus)})")

# Test exponentiation - returns int when both operands are int

power = 2 ** 3

print(f"2 ** 3 = {power} (type: {type(power)})")Run this code and look at the output. Can you see how division always gives you a float, but floor division, modulus, and exponentiation keep the int type when both numbers are integers?

Now test what happens when you mix int and float in operations:

# Test mixing int and float in different operations

mixed_division = 15.0 / 4 # float / int = float

mixed_floor = 15.0 // 4 # float // int = float

mixed_modulus = 17.0 % 5 # float % int = float

mixed_power = 2.0 ** 3 # float ** int = float

print(f"15.0 / 4 = {mixed_division} (type: {type(mixed_division)})")

print(f"15.0 // 4 = {mixed_floor} (type: {type(mixed_floor)})")

print(f"17.0 % 5 = {mixed_modulus} (type: {type(mixed_modulus)})")

print(f"2.0 ** 3 = {mixed_power} (type: {type(mixed_power)})")What do you notice? When you mix int and float, Python converts the result to float because it's the more precise type.

Python Operations Exercise Task

Create a new file called exercise1.py in your labs/lab08/ directory. Write a program that:

- Create these variables:

score1 = 85,score2 = 92.5,score3 = 78 - Calculate the average of all three scores and print both the result and its type

- Convert the average to an integer using

int()and print the difference from the original average - Perform this calculation:

score1 ** 2 / score2 + score3 % 7and print the result and type - Compare what happens with:

int(score2)vsfloat(score1), why the results is liek that?

BODMAS Order of Operations

Python follows the BODMAS rule for order of operations: Brackets, Orders (powers), Division, Multiplication, Addition, Subtraction.

| Order | Operation | Symbol |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Brackets | () |

| 2 | Orders (Powers) | ** |

| 3 | Multiplication and Division (left to right) | *, /, // |

| 4 | Addition and Subtraction (left to right) | +, - |

Let's test BODMAS in your exercise.py. First, compare expressions with and without brackets:

# Compare without and with brackets

result1 = 10 + 3 * 2

result2 = (10 + 3) * 2

print(f"10 + 3 * 2 = {result1}")

print(f"(10 + 3) * 2 = {result2}")Run this code first. Can you see how the brackets completely changed the result? Which operation happened first in each case?

Now test a more complex expression step by step:

# Complex BODMAS example

expression = 3 + 2 ** 2 * 4 - 6 / 2

print(f"3 + 2 ** 2 * 4 - 6 / 2 = {expression}")

# Let's break it down step by step

step1 = 2 ** 2

step2 = step1 * 4

step3 = 6 / 2

final = 3 + step2 - step3

print(f"Step 1 (Powers): 2 ** 2 = {step1}")

print(f"Step 2 (Multiply): {step1} * 4 = {step2}")

print(f"Step 3 (Division): 6 / 2 = {step3}")

print(f"Final: 3 + {step2} - {step3} = {final}")Look closely at this output. Can you follow each step? Notice how Python did the power operation first, then multiplication and division, and finally addition and subtraction.

Test how brackets can change the result completely:

# Same numbers, different brackets = different results

without_brackets = 5 + 3 * 2 ** 2

with_brackets = (5 + 3) * 2 ** 2

different_brackets = 5 + (3 * 2) ** 2

print(f"5 + 3 * 2 ** 2 = {without_brackets}")

print(f"(5 + 3) * 2 ** 2 = {with_brackets}")

print(f"5 + (3 * 2) ** 2 = {different_brackets}")Run this and compare all three results. Can you see how the same numbers give completely different answers just by changing where you put the brackets? This shows why understanding BODMAS is so important.

BODMAS ExerciseTask

Create a new file called exercise2.py in your labs/lab08/ directory. Write a program that:

Restaurant Bill Calculator

A group of 6 friends went to a restaurant. They ordered 3 main dishes at RM25 each, 2 appetizers at RM12 each, and 4 drinks at RM8 each. The restaurant charges a 10% service tax on the total bill, then adds a RM5 delivery fee. Finally, they want to split the bill equally among all friends. Calculate the amount each person needs to pay. Make sure to use BODMAS concept and use floor division to get the amount in whole ringgit (ignore cents).

Assignment Operators

Assignment operators combine assignment with arithmetic operations. Instead of writing x = x + 5, you can write x += 5.

Most of these assignment operators are syntactic sugar - they make your code shorter and easier to read, but they don't add any new functionality. Syntactic sugar is just a more convenient way to write something that you could already do with existing syntax.

TIP

Syntactic Sugar is a term in programming that refers to syntax that makes code easier to read or write, but doesn't add any new functionality to the language. It's called "sugar" because it makes the code "sweeter" (more pleasant) to work with, but the underlying functionality remains the same.

| Operator | Description | Example | Equivalent |

|---|---|---|---|

+= | Addition assignment | x += 5 | x = x + 5 |

-= | Subtraction assignment | x -= 3 | x = x - 3 |

*= | Multiplication assignment | x *= 2 | x = x * 2 |

/= | Division assignment (float) | x /= 4 | x = x / 4 |

//= | Floor division assignment | x //= 3 | x = x // 3 |

%= | Modulus assignment | x %= 7 | x = x % 7 |

**= | Exponentiation assignment | x **= 2 | x = x ** 2 |

Let's test assignment operators in your exercise.py. Start with a score and update it using different assignment operators:

# Test assignment operators

score = 100

print(f"Starting score: {score}")

score += 10 # Add 10

print(f"After += 10: {score}")

score -= 5 # Subtract 5

print(f"After -= 5: {score}")

score *= 2 # Multiply by 2

print(f"After *= 2: {score}")

score //= 3 # Floor division by 3

print(f"After //= 3: {score}")

score %= 15 # Modulus by 15

print(f"After %= 15: {score}")

score **= 2 # Square it

print(f"After **= 2: {score}")Run this code and see how the score changes with each assignment operator. Can you follow how the value changes at each step?

Sequence Control Structures

Python makes sequential programming very straightforward. The Python interpreter reads and executes your code from top to bottom, one line at a time. This is called sequential execution - the most basic control structure in programming.

How Python Interpreter Handles Sequences

The Python interpreter processes your code in a very predictable way:

- Line-by-line execution: Each statement is executed in the exact order you write it

- Immediate evaluation: When the interpreter encounters an expression, it evaluates it right away

- Variable updates: Any changes to variables happen instantly and affect the next lines

Let's see how this works in your exercise.py:

# Sequential execution example

print("Step 1: Starting program")

x = 10

print(f"Step 2: x is now {x}")

x = x * 2

print(f"Step 3: x is now {x}")

y = x + 5

print(f"Step 4: y is now {y}")

result = x + y

print(f"Step 5: Final result is {result}")Run this code and observe how each line executes in perfect order. Can you see how each variable assignment immediately affects the next lines?

Why Sequential Execution is Powerful

Sequential execution in Python gives you complete control over the order of operations:

# Order matters in sequential programming

name = "Ali"

age = 20

student_id = "2024001"

# Build information step by step

full_info = f"Name: {name}"

full_info = full_info + f", Age: {age}"

full_info = full_info + f", ID: {student_id}"

print(full_info)Notice how we build the full_info string step by step. Each line depends on the previous one. Try changing the order of these lines and see what happens.

Proof of Sequential Execution

Here's proof that Python truly executes line by line. Let's create a program with an error at the bottom:

# This code proves sequential execution

print("Line 1: This will run")

print("Line 2: This will also run")

x = 10

print(f"Line 3: x = {x}")

y = x * 2

print(f"Line 4: y = {y}")

print("Line 5: All good so far")

# This line has an intentional error

print(unknown_variable) # This will cause an errorRun this code in your exercise.py. What do you see? All the lines above the error execute perfectly, and you see their output. Only when Python reaches the error line does it stop.

This is different from languages like Java where a single error can prevent the entire program from running. Python's interpreter executes each line as it encounters it, so you get the benefit of seeing results from the working parts of your code.

Try commenting out the error line (add # at the beginning) and run it again. Now everything works perfectly.

Exercise 3: Student Grade System Task

Create a folder called exercise3 in /labs/lab08/. In this folder, create student_grades.py:

A student has taken 5 tests in a programming course. Their grades are 78, 85, 92, 67, and 88. The full mark is 100 for each test and a total of 500 for all test. Calculate the total points, average score, and what percentage each test contributes to the total score. Display the results showing each test score, total points, student average, and what percentage each test contributes to the total score. Use proper variable names and add comments explaining your calculations.

Exercise 4: Fitness Membership Calculator Task

Create a folder called exercise4 in /labs/lab08/. Create membership_calc.py:

A fitness center offers monthly memberships. The base membership costs RM120 per month. Personal training sessions cost RM80 each, and a member wants to book 6 sessions. The gym also charges RM25 for a locker rental and RM15 for towel service. There's a one-time registration fee of RM50 for new members. Calculate the total first-month cost, the monthly cost after the first month (without registration), and the annual cost (12 months including the first month). Use proper styling including variable names and comments.

Exercise 5: Salary Calculator Task

Create a folder called exercise5 in /labs/lab08/. Create two files:

Part A: employee_data.py - Create a module with these variables:

basic_salary= RM4500overtime_hours= 12overtime_rate= RM25 per hour

Part B: salary_calc.py - Import the employee_data module using import employee_data. Access the data using employee_data.basic_salary, employee_data.overtime_hours, and employee_data.overtime_rate. Calculate the total salary with these deductions: 11% for EPF, 0.5% for SOCSO, and 0.2% for EIS. Add fixed deductions of RM50 for medical insurance and RM30 for parking. Display a payslip showing gross salary (basic + overtime), each deduction amount, total deductions, and net salary. Use proper formatting and comments.

Exercise 6: Physics Calculator Task

Create a folder called exercise6 in /labs/lab08/. Create two files:

Part A: physics_constants.py - Create a module containing:

- Standard gravity (9.81 m/s²)

- Ball mass (0.5 kg)

- Building height (25 meters)

- Initial velocity (15 m/s)

Part B: motion_calculator.py - Import the constants module and calculate projectile motion:

A ball is thrown upward from a building at t = 2 seconds. Calculate the ball's position, velocity, and kinetic energy. The ball's motion follows these physics formulas:

- Position = initial_height + initial_velocity × time - 0.5 × gravity × time²

- Velocity = initial_velocity - gravity × time

- Kinetic Energy = 0.5 × mass × velocity²

Display a formatted report showing:

- Initial conditions (height, velocity, mass)

- Time-based calculations (position, velocity at t=2s)

- Energy analysis (kinetic energy at t=2s)

- Motion status (moving up/down based on velocity sign)

Use proper variable naming with snake_case, add detailed comments for each calculation step, and format all outputs with appropriate units and decimal precision.

Push and Check Experimental

After you have finish answering all the questions, make sure to commit and push your files back to your repo.

In the GitHub repo, make sure that the commit passed all the test. Recall back here if you forgot how to check it.